Managing Projects & Teams

How ideas and information disperse in an organisation

Modern businesses have to respond to changing business conditions at an increasing rate. As a result, business processes and team development are becoming more important by the day. As established companies get thrown over by digital powerhouses many are forced to reinvent themselves.

BY NILS WESTHOFF | June 2020

3296 Words | 17 min read

A big part of that reinvention is reimagining the way companies work (Hillenbrand et al., 2019). With many developments in this space, especially since the creation of the Agile Manifesto (Beck et al., 2001), new ways of working have come to light in recent years. Working methodologies of the past (most notably; waterfall) have slowly disappeared in favour of ones that are better at responding to change. This way of working has also changed how ideas and information disperse in an organisation.

This research activity deconstructs organizations atomically. Meaning; we start by looking at the big picture, then zooming in. Thereafter we consider how this influences the way information spreads within an organization.

Agile, Lean & Design Thinking — Better Together

Let's start by looking at modern working methodologies and mindsets. The resistance of large enterprises represses new ideas, and their siloed nature hinders cross-functional cooperation (Cash, Earl and Morison, 2008, pp. 90-100). So, what is the key to a resilient, fast-changing organisation?

Victor Essnert of Doberman (Essnert, Muñoz and Frakes, 2020) explained the issues agile aims to solve. The Agile manifesto favours:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

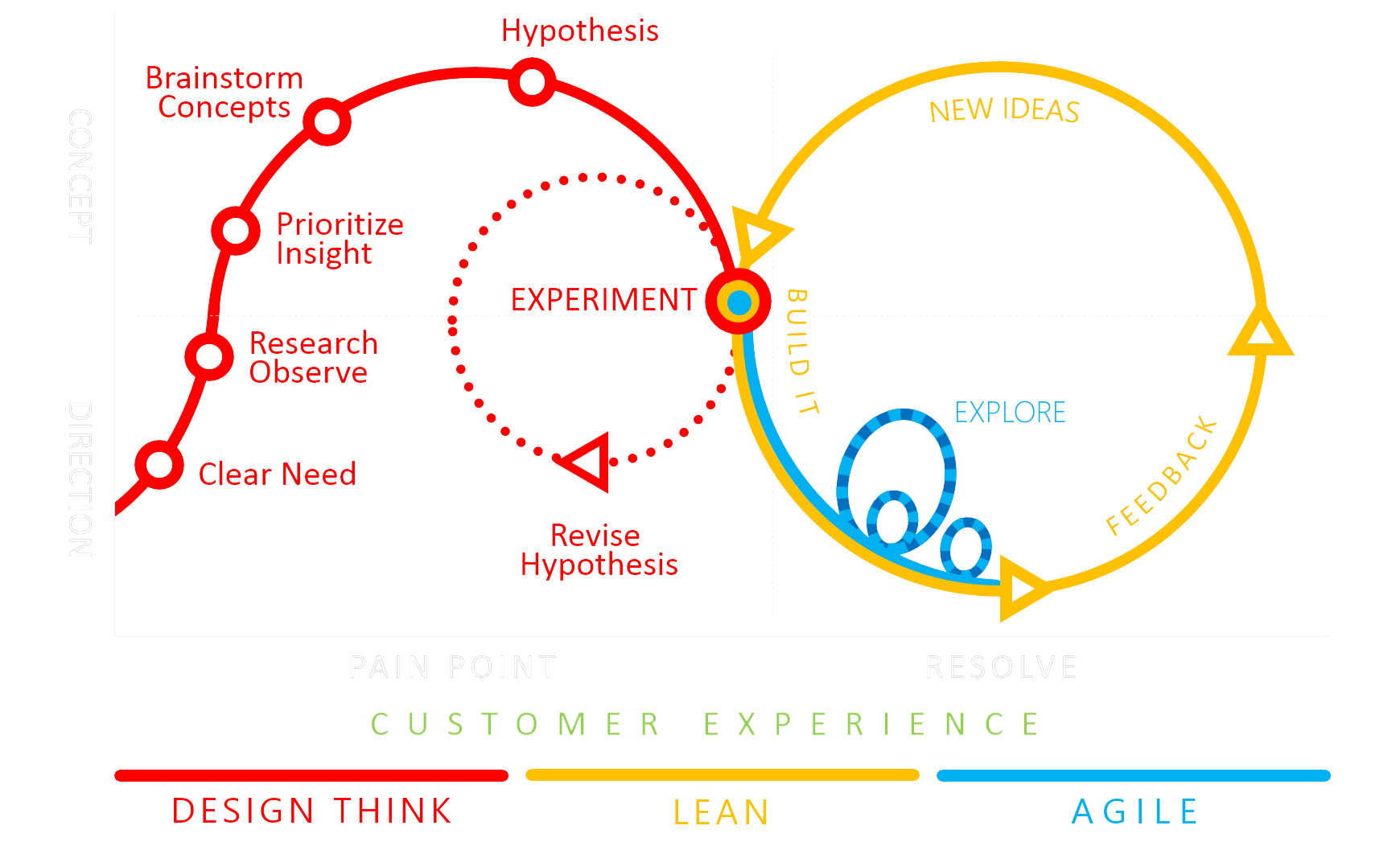

Victor continued his breakdown by showing how Agile works better together with Design Thinking and Lean. He explains how each of these mindsets help us with a mental framework at a specific stage during product development.

- Design Thinking is about exploring and solving problems

- Lean is to test and learn on our way to the right outcomes

- Agile is how we adapt to the ever-changing conditions we work in (especially with software)

At Hyper Island, we've been following many of Agile's principles too. Resilience — being able to respond to change — has been a central part of our curriculum. This has been deeply engrained in the culture of our crew.

What is Culture?

John Seely Brown argues both culture and identity are significant aspects of learning and knowledge (Brown, 2017, pp. 143-144). The culture of an organization is often hard to define. One issue is the invisibility of culture, as described by Spotify's Henrik Kniberg:

Culture tends to be invisible. We don't notice it, because it's there all the time.

- Henrik Kniberg (2014)

Culture is something we have to actively look for in order to understand, analyse and change it.

Vimla Appadoo envisions culture as a bubble that sits around the systems, processes and people of an organization. Culture is what guides us to make decisions about the systems and processes we use. It empowers people to deliver their best work. She also voices three levels of culture, that fit in one another like a babushka doll (Appadoo, 2020b).

- Personal culture: all the things that make us diverse and unique

- Team Culture: how a bunch of individuals work together to produce spectacular work

- Business culture: how lots of teams work together, often united by their values

At Spotify, they favour community over hierarchical structure. Strong community can get away with an informal, volatile structure (Kniberg, 2014). This ultimately leads us into the obvious question; How do we maintain productivity without hierarchical structure? To answer this, we have to look into how autonomy interacts with alignment within organizations.

Autonomy and Productivity

Kniberg says autonomy is motivating and motivated people build better stuff (Kniberg, 2014). That sounds compelling, but how do we ensure the vision of the company doesn't water down? How do we find the right balance between autonomy and being productive? It's easy to be hesitant towards autonomous, self-organised teams. Research addresses a perceived security in following traditional, hierarchical chains of command under the guise of reducing risks and maintaining efficiency (Parker, Holesgrove and Pathak, 2015).

Self-organised Teams

Self-organised teams are self-regulated, semi-autonomous teams. Their members plan and manage their day-to-day activities and responsibilities under reduced or no supervision (Parker, Holesgrove and Pathak, 2015). At Hyper Island I have implemented the daily facilitator, essentially rotating leadership daily. This has been able to tamper louder voices within the team and drawing out responsibility from the quieter ones. This is backed by research as well; imperial (authoritative) leadership is associated with lower levels of voice, cooperation and performance (Erez, Lepine and Elms, 2002). Rotating leadership works by alternating decision control. It harnesses the complimentary capabilities of each team member and deepens and broadens our search for potential innovations (Davis and Eisenhardt, 2011). That doesn't mean top-down leadership disappears completely. However, the role of senior leadership changes.

Autonomy & Alignment

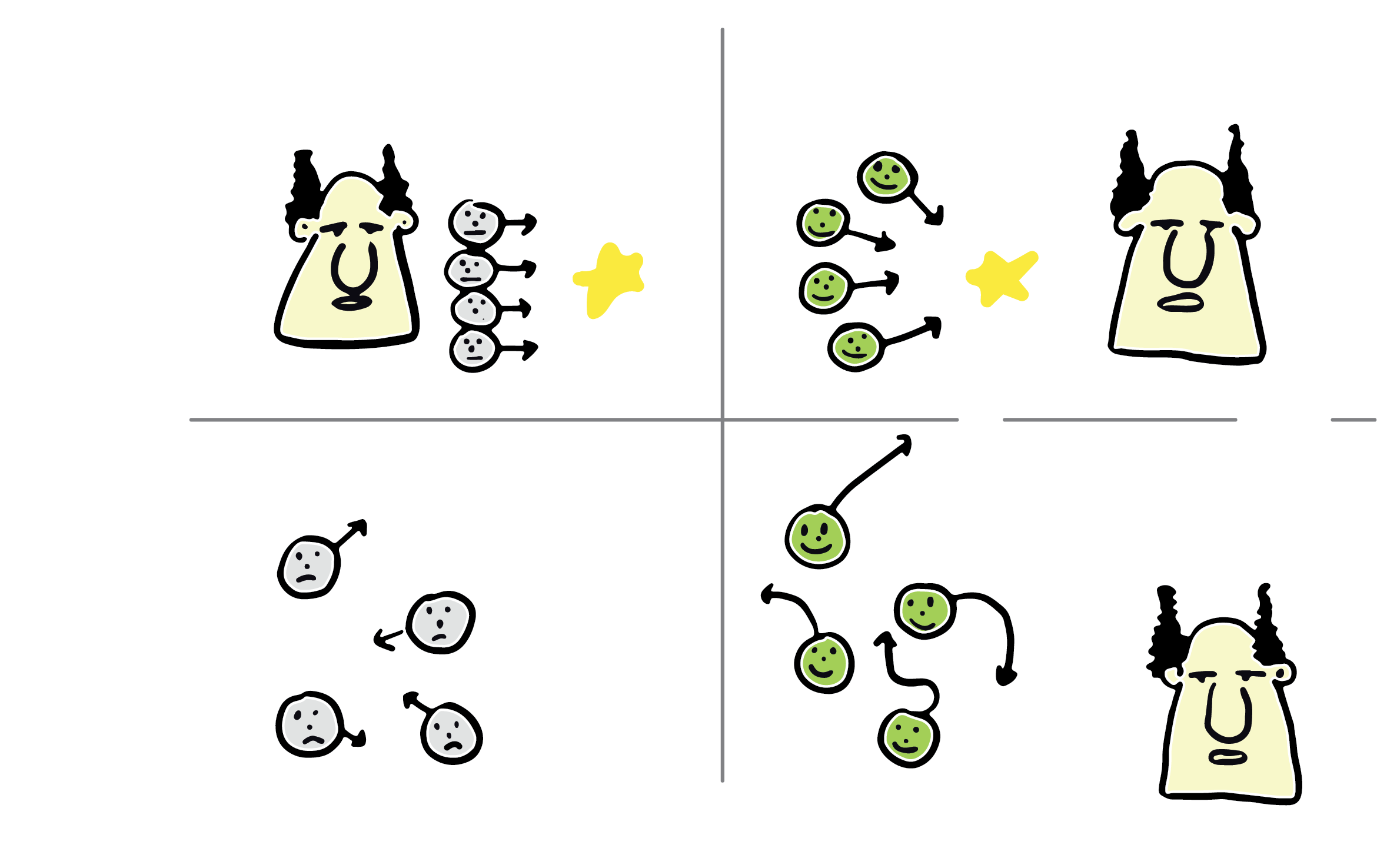

Smith and Sharma think of this in two dimensions; autonomy and alignment. Autonomy is the amount of freedom teams get, to work on the tasks they are motivated by. Alignment describes how all teams work towards the (same) company vision. When alignment is low, teams run in circles like headless chickens. Smith and Sharma define the alignment-autonomy framework. Their framework categorizes the environments at the extremes of these dimensions (Smith and Sharma, 2002).

original by Henrik Kniberg(2014), adapted by me

- Low autonomy and low alignment: a typical micro-management culture; "shut up and follow orders"

- Low autonomy and high alignment: leaders are able to communicate the problem but also tell people how to solve it.

- High autonomy and low alignment: teams do whatever they want, leaders are helpless and the product becomes a Frankenstein

- High autonomy and high alignment: leaders define the problem, but let the teams figure out how to solve it

Spotify details how they apply this knowledge in practice. The last environment, one of high autonomy and high alignment is what they call aligned autonomy. Effective leadership for them is about creating strong alignment, which affords them to grant more autonomy to their teams (Kniberg, 2014).

Harmonizing as a team

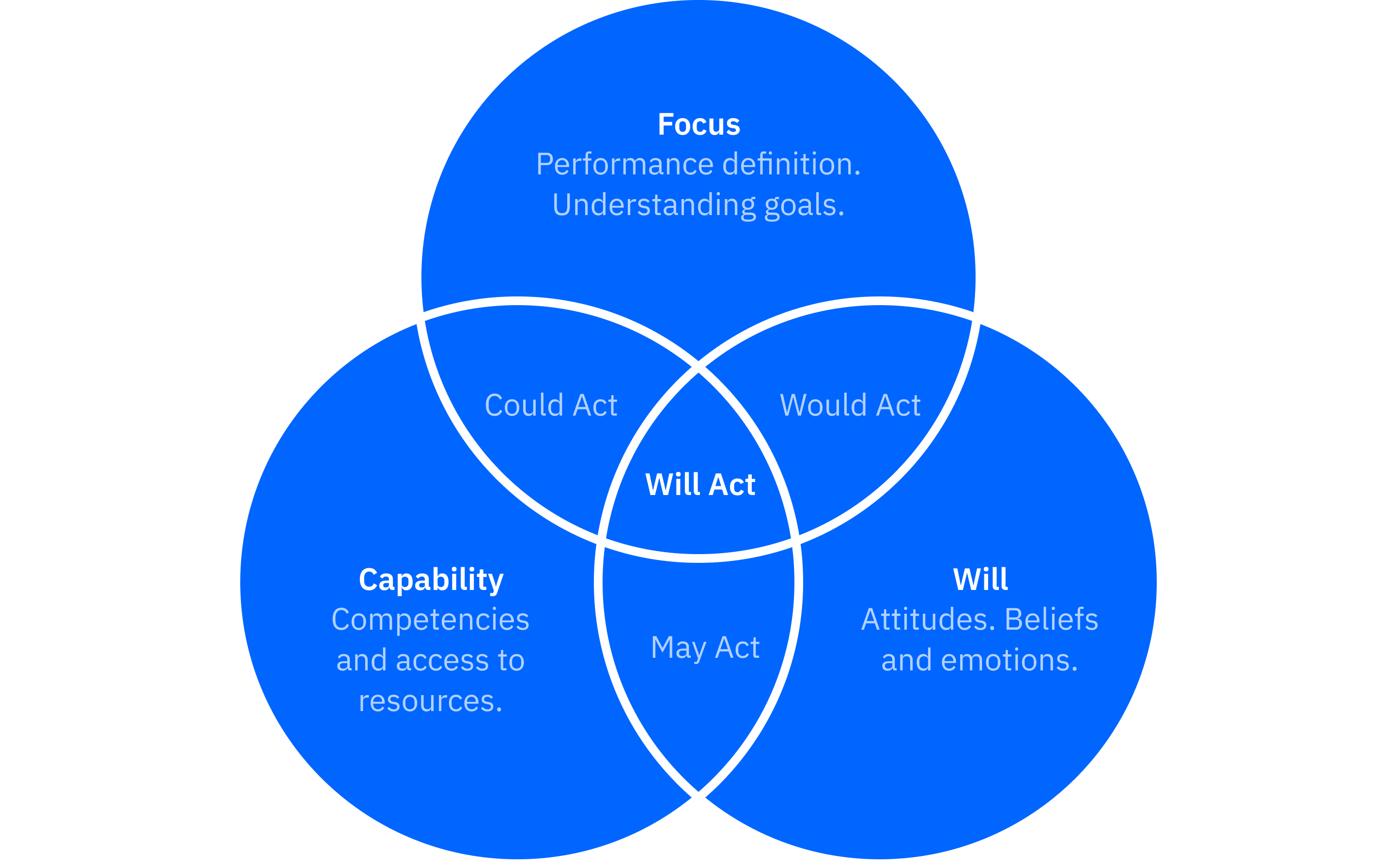

On a smaller scale, individuals must develop a responsibility and leadership. Smith and Sharma define three key elements that, once appropriately defined, attract leadership and responsibility (Smith and Sharma, 2002).

original by Peter Smith and Meenakshi Sharma (2002), adapted by me

- Focus: defined and clear goals for the business and team

- Will: finding meaning and purpose in the work

- Capability: adequately skilled team members, availability of resources

Adequately defining these elements naturally promotes decentralized leadership and enables autonomy of working teams.

Shaping Work

Shape Up solidifies lots of these ideas. Ryan Singer describes how management 'shapes' the work. 'Shaped work' hits the right balance between concrete and abstract. To Singer, the right level of abstraction is:

[C]oncrete enough that the teams know what to do, yet abstract enough that they have room to work out the interesting details themselves.

- Ryan Singer (2019)

Shaped work shouldn't define what the result looks like, but should clearly define the intended functionality or goal. They are clearly defined, rough ideas. Moreover, they define creative constraints and specify where the work ends. Shape Up enforces this by a mechanic Singer calls appetite. Appetite settles how long we are willing to spend on the work. It makes us ask ourselves how much time this idea is worth to us, before mindlessly starting the work because we're excited about it (Singer, 2019).

I've noticed that I've been doing something similar at Hyper Island too (especially during later projects). Our team would define tasks with some level of abstraction and refining the work individually or in smaller groups. We've essentially been shaping our own work together, which enabled us to divide work effectively. A prerequisite for this to succeed is that we trust each member will put in the work. The Hyper Island curriculum has handed us several tools to align as a team, underpinned by Susan Wheelan's theory for creating effective teams.

Effective Teams

How team members behave is critical to the success of the team and significantly affects how knowledge is received. There are many factors to take into account when compiling a new team. What would an effective team look like? How should they act? Who are the people in an effective team?

Team Development

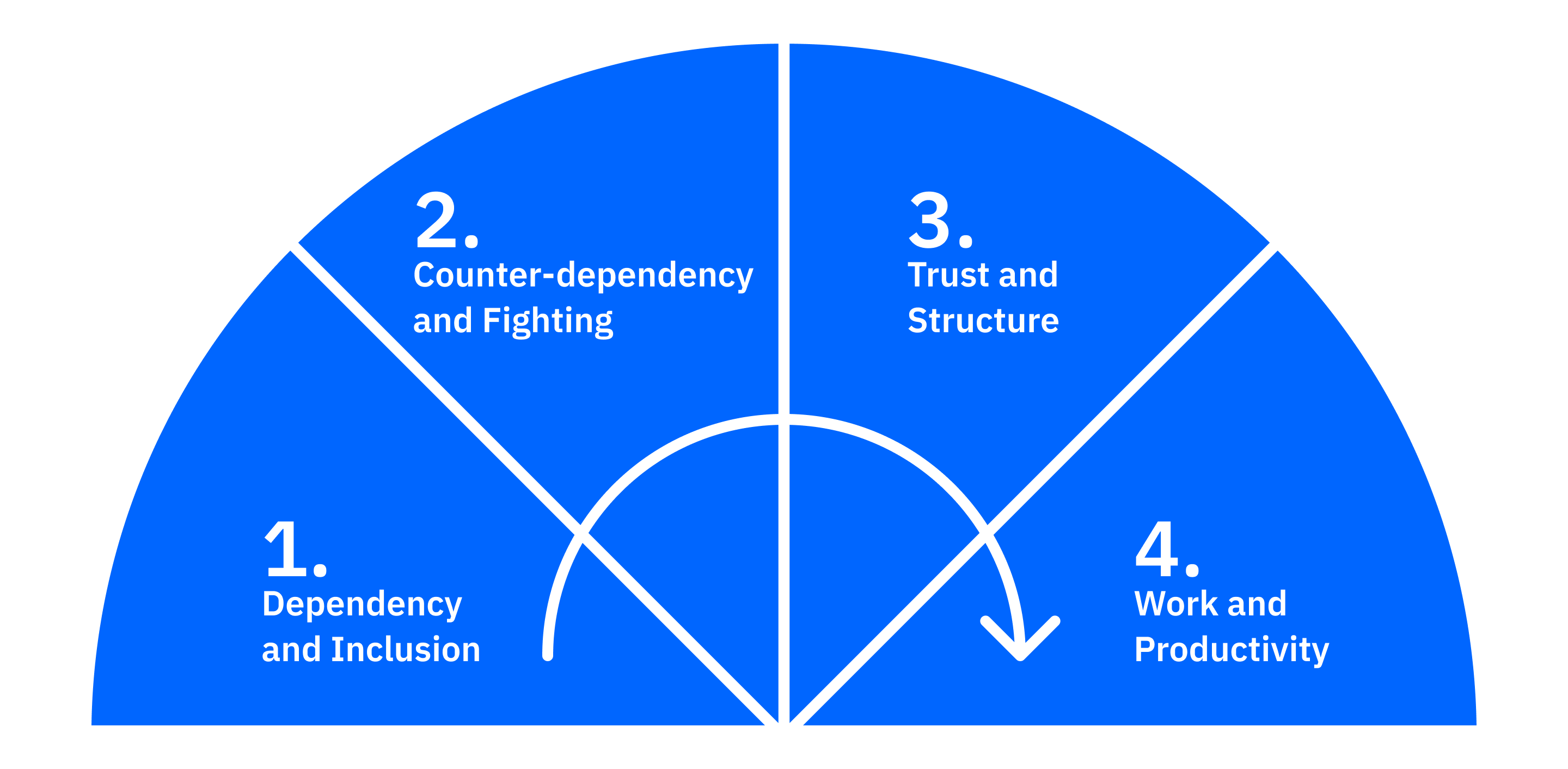

One lens to increase our understanding of effective teams is Wheelan's Integrated Model of Group Dynamics (IMGD). She defines four stages of group development (Wheelan, 2016).

original by Susan Wheelan (Wheelan, 2016)

Dependency & Inclusion

Teams get to know each other. Finding out and understanding about the group's objectives, values and rules.

Counter-dependency & Fighting

Subgroups form. Competitiveness and conflicts increase in team.

Trust & Structure

Objective is clear. Team understands how to deal with conflicts. Cooperation and collaboration.

Work & Productivity

Team solves problems collectively. Decisions are made as a group. Safe space to speak freely.

Teams working together move through several stages as they continue working together. Team development looks different for every team and won't necessarily happen in a linear fashion. They may go through all of these stages, or only a few. Many groups will get stuck at some point. Even teams that have been working together effectively for a long time may (temporarily) regress as well.

Team Termination

Additionally, Wheelan (2016) defines a fifth stage; termination. While this technically isn't a development stage, it's still an important step in team development. By consciously disbanding a team, we extract our learnings and give team members a sense of closure. Team termination concerns the evaluating the performance of the group and acknowledges the success the team has had.

Focus of Effective Teams

Furthermore, Wheelan (2016) determined effective teams focus on 10 things:

- Goals

- Rules

- Interdependence

- Leadership

- Communication and feedback

- Discussion, decision making and planning

- Implementation and evaluation

- Norms and individual differences

- Structure

- Cooperation and conflict management

In summary, effective teams communicate their needs and wishes. They rely on each other to improve and know what to expect of each other. Effective team members respect each other's differences and have systems in place to improve themselves as well as others.

Constructing an Effective Team

With these points, Wheelan (2016) address what effective teams focus on. However, it does not tell us anything about the building blocks of an effective team, the people within it. Decades of research show socially diverse groups are more innovative than groups that lack diversity. Groups with a diversity of race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation are better at solving complex, nonroutine problems than homogeneous groups (Phillips, 2014). Simply interacting with individuals with unique perspectives, makes people weary of potential differences. Non-diverse groups perceive unique information as straight-forward and generally spend less time on a task, often rushing to the wrong solution (Phillips, Northcraft and Neale, 2006). By working in a diverse team, we are forced to prepare and anticipate alternative perspectives, before reaching consensus.

Group Flow

Flow is a well established concept in psychology introduced by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1991). Flow is defined as an optimal experience; a challenging activity that requires skill. Activities that put us in a state of flow are goal-directed and bounded by rules. When this state is reached, it completely consumes what we're doing and makes time pass without us noticing. Sawyer studied this concept within groups (Sawyer, 2008). He outlines ideal conditions for group flow as:

- Group goals

- Close listening

- Complete concentration

- Being in control

- Blending egos

- Equal participation

- Knowing team mates

- Good communication

- Being progress-oriented

People experience flow most commonly when in conversation with others, Csikszentmihalyi found. When this occurs, statements are genuinely unplanned responses to what we hear (1991). Consequently, group flow is more likely to emerge when everyone is fully engaged — at Hyper Island we do this by active listening (Sawyer, 2008).

Communication

Communication is the fabric that connects how people live and work. Basecamp, a company that works 100% remotely, spends a lot effort to improve team work, culture and communication. In their list of principles, called "How We Communicate", co-founder Jason Fried writes:

Few things are as important to study, practice, and perfect as clear communication

- Jason Fried (2019)

Fried seems to be focused on reducing communication, favouring asynchronous modes of communication over meetings. Though I think studying the way we communicate can be done on a wider scale. Speaking the same language as our team mates is a big part of that.

Project & Reflect

Appropriately kicking off new projects (with a new team) can significantly impact the perception team members have on the work ahead. By projecting ourselves forward and opening a conversation on the previously mentioned focus, will and capability, teams are able to foster leadership from within (Smith and Sharma, 2002). Concretely; by defining team purpose, desired outcomes, values, roles and skills with the team we're more resilient to potential issues that lie ahead.

During and upon concluding projects, there are opportunities to reflect. This creates space to think and share how we work as a team. By forcing team members to put their fears and anxieties on the table, individuals are able to relate better to one another. By creating this open space within the group we become aware of (shared and unique) unmet needs. Furthermore, team members become more comfortable with sharing deep feelings. The reciprocity of sharing fears forms trust. The trust to share (unfinished) ideas too, effectively stimulating creative output.

Asynchronous

People are social creatures, so at the same time it is easy to over-communicate as well. Communication in a working environment easily interrupts work and valuing each others' time is vital. Updating team mates on progress is important, but asking them to follow every step of the way is a distraction. At Basecamp they are big advocates of asynchronous communication.

Real-time sometimes, asynchronous most of the time.

- Jason Fried (2019)

Their main argument is that verbal means of communication cost more time to multiple people. During meetings, the barrier to interrupt an argument is lower, which easily spins a discussion away from the goal at hand.

Writing solidifies, chat dissolves.

- Jason Fried (2019)

While not everyone will agree with me, in my personal work at Hyper Island I've experienced this as well. Sharing research often played out as listing everything we had found, which often messed with our planning. I suspect sharing individual work through writing or drawing would have prevented interruptions and delayed questions or judgement. The discussions we'd have had would have been more meaningful and focused. Definitely something I'm willing to try in the future.

Balance

It's good to be weary that it's possible to under-communicate too. Vimla Appadoo, guest speaker at Hyper Island, bravely shared one of her biggest mistakes starting at her new job was:

Over doing and under communicating

- Vimla Appadoo (2020a)

She mentions how she used to work in isolation, fixated on doing the work. Leading to the alienation of some co-workers, especially those unfamiliar with design practice. As previously established, conversation is an environment where lots of people find flow. While I'm certainly in favour of effective communication, unstructured and casual watercooler conversations are also a source of new ideas and sharing knowledge. Conversation is where information meets, crosses boundaries and where new ways of thinking flourish.

Collective Intelligence

At larger organizations there is little chance of a common identity. The people within them are too diverse, engaged in different tasks and spatially disconnected. Information and knowledge forms locally and is stored in a decentralized clusters, as John Seely Brown explains in The Social Life of Information (2017, pp. 144).

[A] work identity, even in multinational firms, is to a significant degree formed locally, where practitioners work together and practice is interdependent.

- John Seely Brown (2017, pp. 144)

Brown suggests ideas emerge where people come together. Interconnected clusters of people diffuse ideas through different organizations.

How we becomes better than me

Let's regard the knowledge within an organization as a collective brain. Suddenly it becomes useful to connect its neurons and synapses in as many directions as possible. The shorter the connection to useful information is within an organization, the easier it is to access and harness it. I think this is a partial explanation of Spotify's successful culture. Day-to-day work is done in cross-functional teams. Though they are connected through larger collections of teams (called tribes) and coached by function. There are lots of opportunities for knowledge to spread and thrive. Their culture favours cross-pollination over standardization. In an environment like this, only the strongest connections survive (Kniberg, 2014).

Our Hyper Island crew has slowly started connecting their knowledge in a similar fashion, albeit at a smaller scale. Each member in our crew has worked in several teams now, connecting knowledge from previous experiences to the next. It has linked our varying skillsets throughout the crew. A concrete example is how both masters, Digital Management and Digital Experience Design, have worked together and shared their lens into the world with each other.

Remote

Work-from-home has been slowly gaining traction over the past few decades (Felstead and Henseke, 2017). This year we have all — unfortunately had to — become experts at remote work. Nowadays, we're blessed by high speed internet and the existence of online collaboration tools. Tools like Zoom, Miro and Keynote Live allow us to keep working together, even when physically apart.

Watercooler Moments

Unfortunately these tools do not reduce the distance between us. They're unable to solve some of the problems this separation creates. Virtual environments deprive us from the learning we used to get from peers beyond project work (Brown, 2017, pp. 140-145). Rob Potts (programme leader at Hyper Island) emphasized the importance of these watercooler moments we used to have while working together in the studio. We used to bump into each other by chance, we'd talk about how awful the water tastes in the UK and discussed what to eat for lunch. Remote collaboration lacks our desire to instantly and spontaneously bond over something as simple as coffee (Gorlenko, 2005). The absence of behavioural cues force us to rely on verbal communication mostly. Adjusting to this new reality is clearly more difficult to some than others.

Remote Intensity

While working-from-home generally shows higher job satisfaction and job-related well-being, the current circumstances likely dampen many of these benefits. Simultaneously remote employees show higher commitment and are generally more task-focused. We work in the same space as we eat, sleep and live in. The way we experience work intensifies and it's harder for us to switch off from work (Felstead and Henseke, 2017).

Ultimately, we have to recognize the differences remote work creates. Agile companies are more likely to successfully adapt and overcome these issues. I'm interested to see how society changes as a whole. To learn about the way we learn from each other in a distributed workforce.

Conclusion

I used to think the strongest argument the Agile manifesto poses is being ready to change. I do think however, that after my experience at Hyper Island and analysing modern businesses practices, this has changed a bit. Resilience to change is not a goal, but an outcome. Not only are modern businesses learning more iteratively than before. They interconnect knowledge more effectively throughout their organisation. This has empowered these businesses to respond to change better than companies sticking to less flexible working processes.

Part 2: Team experiences

The second part of this research activity is a group effort to reflect on our individual- and group experiences during the first three modules of our Hyper Island curriculum.

Download as PDF Download as Keynote